I have always been an admirer of the paintings by Jheronimus Bosch. His works – like those of Bruegel – are like ‘find Waldo’ plates, riddled with strange creatures, humor and symbolism. It’s easy to fill an evening staring at one of these paintings. It never gets boring; very time you look at it there is something new to catch your eye.

I have always been an admirer of the paintings by Jheronimus Bosch. His works – like those of Bruegel – are like ‘find Waldo’ plates, riddled with strange creatures, humor and symbolism. It’s easy to fill an evening staring at one of these paintings. It never gets boring; very time you look at it there is something new to catch your eye.

Because in 2016 it’s 500 years since Bosch died, there are a lot of events in his home town Den Bosch. It started with a large exhibition in the Noordbrabants Museum, where they gathered 20 paintings and 19 drawings by the old master. Almost all surviving artworks. In the short time the museum was open, over 400.000 visitors attended.

At the Crafts-weekend in the Hernen Castle last fall, a man approached me with the question if I would be interested to attend an event called “The World of Jheronimus Bosch“. A reenactment event held at the 4th and 5th of June in Den Bosch. I replied that it already was my intention to live in the museum for a week…

Instruments

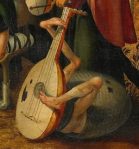

Bosch used a lot of instruments in his paintings. Often with an allegorical meaning, reminders of vanity and debauchery. In ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights” we see a lute, harp and hurdy gurdy used to torture lost souls in the hell…

Bosch used a lot of instruments in his paintings. Often with an allegorical meaning, reminders of vanity and debauchery. In ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights” we see a lute, harp and hurdy gurdy used to torture lost souls in the hell…

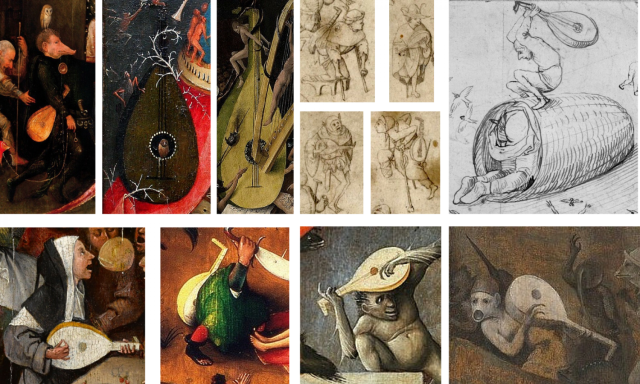

But I would like to focus on the lutes for a moment. There is a number of them in his paintings and drawings. I compiled this small selection.

Let’s conclude that there are a lot of creative ways to use a lute other than for playing…

But there are more lute depictions that can be related back to Bosch. Like this example in ‘The Concert in the Egg’ made by a follower, probably after a drawing by the old master. How maybe times have you seen a donkey with a black hat playing a lute before?

But there are more lute depictions that can be related back to Bosch. Like this example in ‘The Concert in the Egg’ made by a follower, probably after a drawing by the old master. How maybe times have you seen a donkey with a black hat playing a lute before?

This detail of another “Fight between Carnival and Lent“, considered to be a 16th century copy of a lost painting by Bosch. The player sits in a broken bagpipe… More about this painting and its symbolism in a later blog…

This detail of another “Fight between Carnival and Lent“, considered to be a 16th century copy of a lost painting by Bosch. The player sits in a broken bagpipe… More about this painting and its symbolism in a later blog…

Or this example by Jan Mandijn in his version of ‘The Mocking of Job’ (ca. 1540-1550). Who would have thought that you could play a broken lute with your feet? Maybe some rock players aren’t so original after all?

Or this example by Jan Mandijn in his version of ‘The Mocking of Job’ (ca. 1540-1550). Who would have thought that you could play a broken lute with your feet? Maybe some rock players aren’t so original after all?

But all kidding aside: whenever I see an instrument in a painting it always leaves me wondering how it would have sounded. Paintings like these can be a rich source of inspiration.

I often quickly suppress the idea of making a reconstruction, because projects like that tend to explode. But it usually lingers on in the back of my mind…

To make a reconstruction

The lutes Bosch depicted all have a sort of pear-shape. To a trained eye they look quite archaic, naïve even. Somehow a bit like the ‘Van Zwolle’-manuscript, the first European description of a lute we know. But when I looked deeper into it the shape reminded me more of this statue of the so called ‘Ulm Pythagoras’.

I found a picture of this sculpture in an old history book years ago, and it has been at the wall in my various workplaces ever since. Knowing that it would come in handy one day…

I found a picture of this sculpture in an old history book years ago, and it has been at the wall in my various workplaces ever since. Knowing that it would come in handy one day…

The shape of this lute is quite close to that of the Bosch models. A circle shaped base, with two longer compass arcs that make the shape towards the neck. But the one thing that really got me on track was the research on early ouds by John Downing (published on ‘Mikes Oudforum’ and in Fomrhi Quarterly). He found that the shape of the ‘Ulm’ lute was based on the ‘Pythagorean Triangle’. This triangle has side lengths of 3, 4 and 5 units long and thus adheres to the Pythagorean theorem of a²+b²=c² ( or in this case 3²+4²=5²).

But the one thing that really got me on track was the research on early ouds by John Downing (published on ‘Mikes Oudforum’ and in Fomrhi Quarterly). He found that the shape of the ‘Ulm’ lute was based on the ‘Pythagorean Triangle’. This triangle has side lengths of 3, 4 and 5 units long and thus adheres to the Pythagorean theorem of a²+b²=c² ( or in this case 3²+4²=5²).

Medieval lutes

Unfortunately no examples of medieval lutes survive. They have fallen prey to the ages. One surviving lute (the Georg Gerle of 1581) is thought to be a copy of an earlier form of lute, it was preserved in a wunderkammer of a castle. But this 6-course example is closer to the ‘Kana Wedding‘ picture by Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen (ca. 1530) than to the late medieval models painted by Bosch.

In absence of surviving examples, we have to rely on pictorial evidence and written sources as basis for a reconstruction. Fortunately these are legion, like this painting by Hans Memling (ca.1480)…

or these woodcuts by “Master BXG” (ca. 1470-80)

and Israhel van Meckenem (ca. 1490)

Most reconstructions of medieval lutes have a 4 course disposition. Occasionally you will spot a 5 course example. I think five courses would be most appropriate for the Bosch model. Because it’s right between the earlier four course lute of Van Zwolle (ca. 1440) and the six course depicted by Vermeijen (and the Bolognese models by Hans Frei and Laux Maler). Throughout history the number of courses increases gradually.

To make the reconstruction I started by determining the unit of measurement used in Den Bosch at the time of Jheronimus. A “Voet” (foot) divided in 10 “Duimen” (Thumbs) that are broken up in four “Kwartieren” (Quarters). With a reconstruction of this ruler, I started drawing a plan. A little bit different than normal (in a CAD program) but with an old school square, ruler, pencil and compass…

The result was this drawing, inspired by the Van Zwolle manuscript.

The description was written in Dutch, with quill and ink. The paper was a little bit aged afterwards.

After the design was ready a form could be made. Van Zwolle speaks of a ‘skeleton’ or ‘rack’ type of mould, rather than a solid model.

For me it’s the first one I make in natural wood (reclaimed from furniture) instead of plywood… Wonder how it will work.

Stay tuned for more on this lute. I will try some unconventional ideas, along with old techniques…

The lute and tools used will be a part of my reënactment kit, in an attempt to make a reconstruction of all elements in the “Lautenmacher” engraving by Jost Amman.

When I read the title of this post I half-expected to find something not dissimilar to my own instruments (two survivors, one scrapped)

LikeLike

Enjoyed the read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very interesting article!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person